Hilda Stuart turned down a coffee

refill at Legend’s Steakhouse in Smyrna — no fault

of the coffee — and then she thought for a moment. Hilda Stuart turned down a coffee

refill at Legend’s Steakhouse in Smyrna — no fault

of the coffee — and then she thought for a moment.“I guess I saw things different from everybody else,” said Stuart, who is known to country music fans as Marty Stuart’s mother but whose new book of photographs, Choctaw Gardens, marks her as someone who, indeed, “saw things different from everybody else,” and who captured those things with an artist’s eye and a cumbersome Ansco camera. “I just figured looking ahead that there wouldn’t be any baptisms in the creek anymore, or many reunions at the old places,” she said. “I’m 79 years old, so this goes way back, and I saw things changing. I figured if I documented those things, my kids would know who their grandmothers were.” Choctaw Gardens (Nautilus Publishing) means we can all know who Marty and sister Jennifer Stuart’s grandmothers were, and the photos reveal something about the woman behind the camera, as well. Photos of record  Hilda Stuart’s devotion isn’t just to

documentation, it’s also to illumination, in a

couple of ways: Technically, she wants to make sure

the lighting is right. And if the lighting is right,

and the photographer is perceptive, the subjects of

the photographs are illuminated. They are clarified,

and elucidated. They are better understood. Hilda Stuart’s devotion isn’t just to

documentation, it’s also to illumination, in a

couple of ways: Technically, she wants to make sure

the lighting is right. And if the lighting is right,

and the photographer is perceptive, the subjects of

the photographs are illuminated. They are clarified,

and elucidated. They are better understood.Because of Marty Stuart’s prominent place in country music, Hilda’s photographs of him as a child carry a historic value in addition to their artistic value. And he is illuminated in these pages. Anyone who doubts his devotion to sounds and song can be disavowed of that notion in one moment of Choctaw Gardens viewing. Here, we see him nearing 2 years old, wearing a cloth diaper and mimicking a neighbor lady playing the piano. We see him at 11, beaming brightly, on the arm of country star Connie Smith, who had come to the Choctaw Indian Fair in Philadelphia, Mississippi for a personal appearance. Marty and Jennifer Stuart had their photo taken with Smith at the show. And, 17 years later, Stuart and Smith married. And we see some particularly evocative shots from 1972, the year Marty Stuart turned 14, left Mississippi and came to Nashville to play in Lester Flatt’s Nashville Grass band. There’s Marty onstage at the Grand Ole Opry, and signing autographs for a circle of children and teens in the alley outside Ryman Auditorium. There’s Marty sharing a microphone with Father of Bluegrass Bill Monroe in Heber Springs, Arkansas. Hilda, Jennifer and father John Stuart wouldn’t move to Nashville until 1974, so 1972 and 1973 brought delight at a son’s precocious talent and sorrow at his removal from the tight-knit family. “It was hard,” Hilda says. “You want your children to do what they want to do, and people are happy when they find their niche. When he was in sixth grade, Marty wrote an essay at school and mapped out everything he’s doing right now — gold records, a bus, everything except for marrying Connie. After he saw her at the fair, he added marrying Connie. I kept that essay, put it in a lock box. It bugged me that day, though. I thought, ‘Hmmm, where is this leading?’ “When Lester wanted Marty to join the band, it was a little bit early. But if we’d said, ‘No,’ maybe he wouldn’t have gotten that chance again.” And so she visited Nashville when she could, and took photos when she visited. Film was expensive, as was developing film, and so she was careful, examining first and shooting after all essential elements were in line. And then she mailed rolls of film to Meridian, Mississippi for developing. “It was a big thrill when you got those pictures back in the mail,” she says. “You opened that package up and it was, ‘Ah, did I get any images?’ And usually, I did. I didn’t miss too much.” Signs of the times  She didn’t miss her son’s ascent into

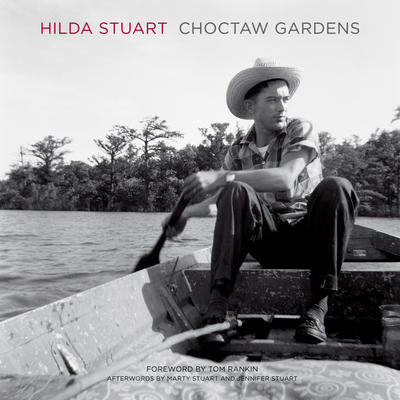

professional music-making, or her husband’s

determined rowing on a fishing boat in the

Mississippi Delta. She didn’t miss the cotton fields

where she skipped two school weeks each year of

childhood in order to participate in a harvest that

she dreaded all year. She didn’t miss baptisms at

Levi Stuart pond or a rare snow day in Philadelphia.

And because she didn’t miss those things, we don’t

have to, either. She didn’t miss her son’s ascent into

professional music-making, or her husband’s

determined rowing on a fishing boat in the

Mississippi Delta. She didn’t miss the cotton fields

where she skipped two school weeks each year of

childhood in order to participate in a harvest that

she dreaded all year. She didn’t miss baptisms at

Levi Stuart pond or a rare snow day in Philadelphia.

And because she didn’t miss those things, we don’t

have to, either.Today, Hilda Stuart sees people taking pictures all the time. They hold up their phones and document their breakfasts, their children, their spouses and their pets. Our days now pass in a barrage of digital images, yet we still wind up lacking focus. Hilda Stuart has a digital camera, but she doesn’t use it much. “I’ve been getting the old Ansco out,” she says. “It’s a little complicated. But there’s something about the detail in the color. If it’s focused right and the lighting’s good, there’s something in there that the digital ones don’t pick up.” That doesn’t mean there’s any holiday clamor for old Ansco cameras. Most of us are happier with Androids and iWhatevers and other things that let us text and update and otherwise distract ourselves while we take our photos. And we’re probably right. It’s just that Hilda Stuart sees things different from everybody else. By

Peter Cooper

|